Be it in ethnographic studies, film documentary or photojournalism, empathy, as much as plain observation, come into play.

Empathy comes from patience – the patience to sit down with your interviewees and subjects, to absorb their lives and understand what it is they go through before you snap a photo.

In photojournalist Candace Feit’s case, patience has been a virtue.

As a photojournalist since 2004, Feit has developed a sense of compassion with the communities she works with around the world. They’re not merely “subjects” she captures on assignments, but rather, newly found friends and people she can relate to, and ultimately, people who invite her in.

Her work has been frequently featured in the New York Times, as well as Le Figaro, Chicago Tribune and countless travel and culture magazines.

In 2013, Feit made two one-week trips to India’s state of Tamil Nadu to spend time with the kothi community, or queer community, which has struggled to gain wider social acceptance.

The term kothi widely describes a group of identities and relationships, including “married fathers who have male lovers, people born male who dress like females and male-born people who wear traditional women’s clothing only during religious festivals or celebrations”, says Feit.

The South Africa-based photographer used her time while she was there to tell their story through stunning visuals captured on film, in all its enchanting colour and grainy authenticity.

Her documentation raised attention at a time when India’s Supreme Court in December upheld Section 377 of the Indian Penal Code, which criminalises homosexual acts, and as activists around the nation sought to repeal the law.

And while the law has not been been forcibly applied it has, as Feit says, brought about instances of harassment and abuse against India’s queer communities.

In an interview with Contented via email, Feit, who is occupied with her new project focusing on the visual aspects of “Americana” in the US, took time to walk us through part of her process documenting the community, which she intends to revisit again this September.

You photographed in film and in low-light. What were some of the difficulties and what were you using?

I photographed using a Hasselblad with 120mm film – 400ISO usually.

It is technically challenging to capture things at low light, but I’ve worked with this camera setup for years and I wouldn’t feel comfortable shooting any other way. The Hasselblad and film forces me to slow down significantly, which makes me feel far more connected to my subject in the moment. The way I work is almost never fast. Especially with projects like this one, I spend the majority of time hanging out, chatting, just observing people before I take any photographs.

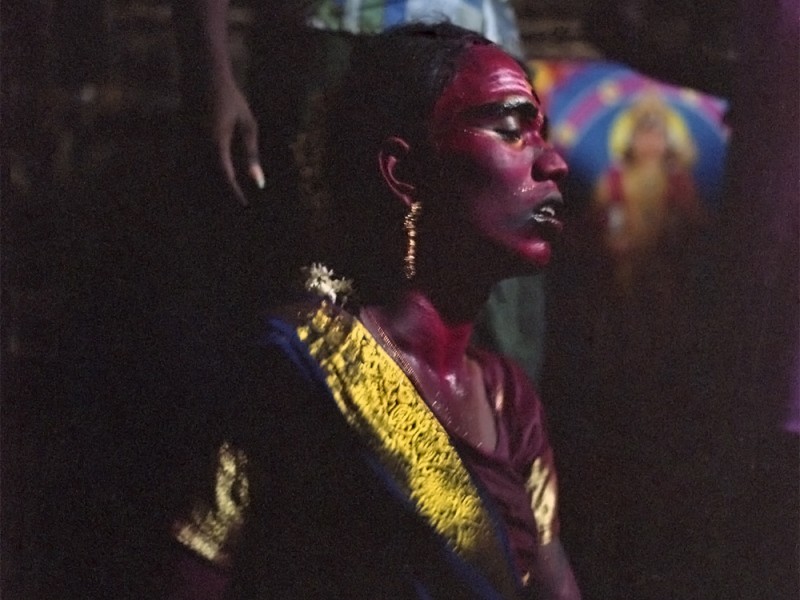

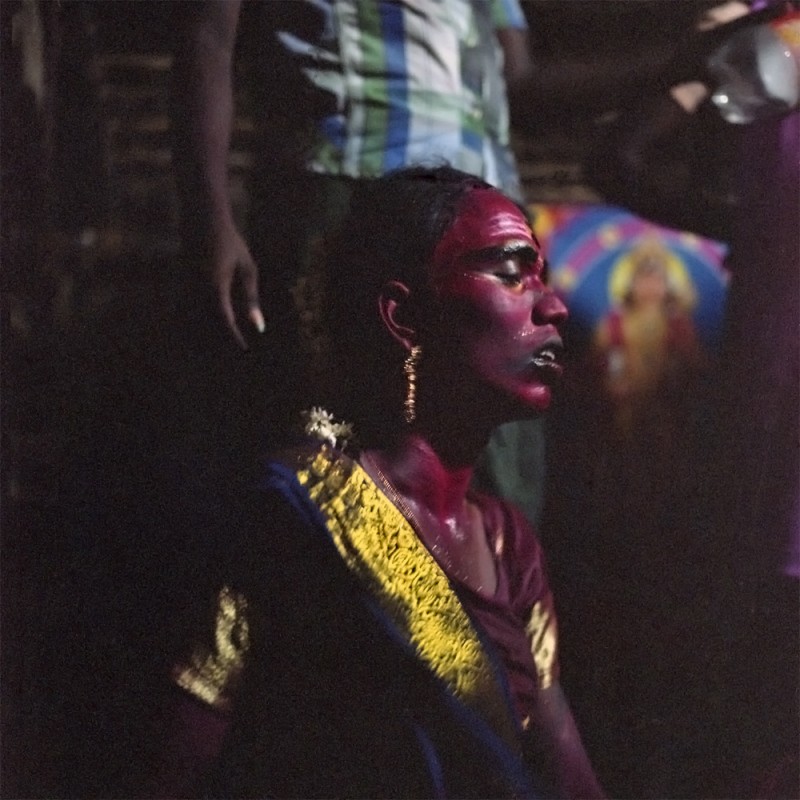

You have a recurring character in your photos, a temple priestess. Tell us more about her and her family. There seems to be a happiness and a sense of hope on her face from the photographs you took.

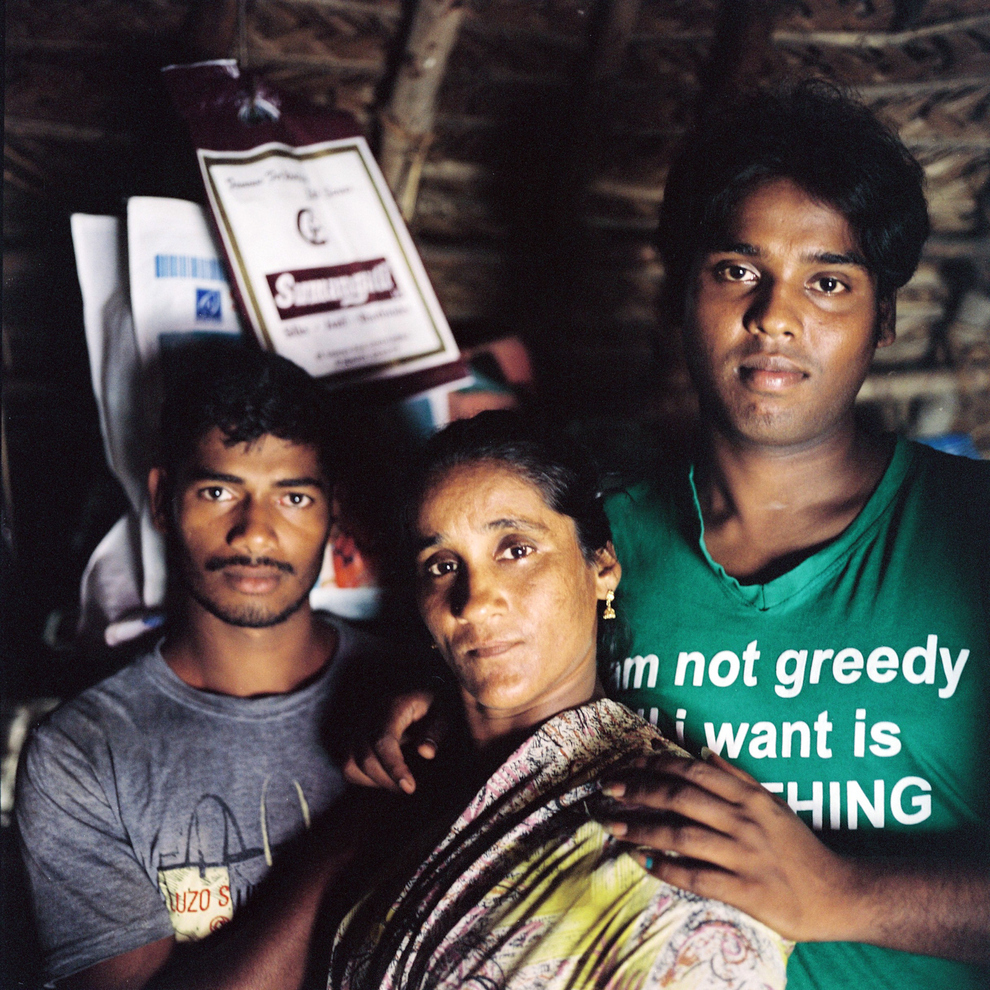

The temple priestess is named Sivagami. She is a very well-respected member of the community and has been a priestess for several years. She was leading much of the rituals for the festivals. She currently lives with her mother and has close ties to the other kothis in the neighbouring communities. Her house also tends to be a gathering place for members of the community.

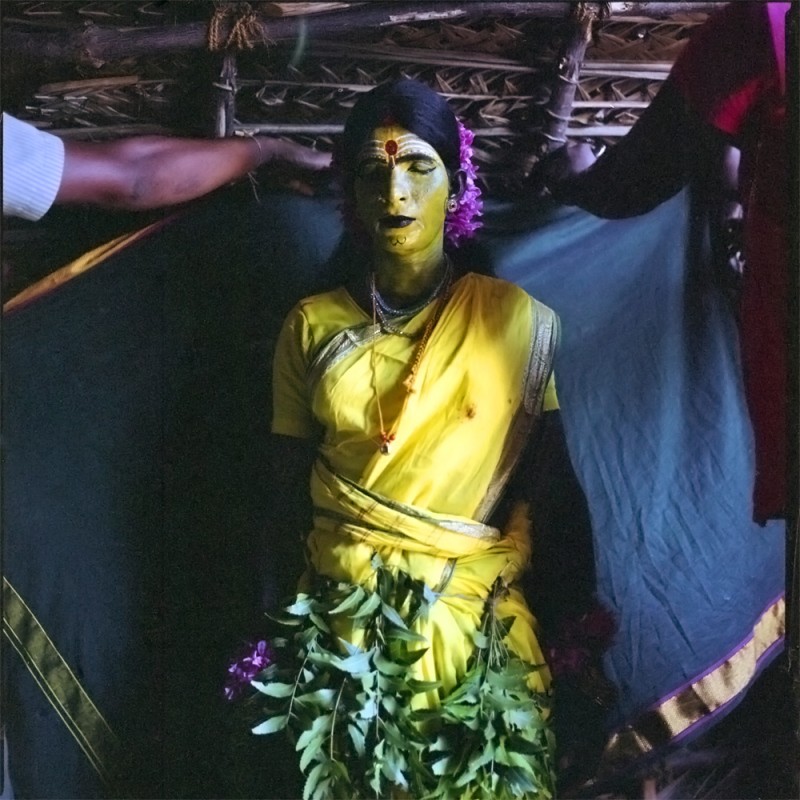

Tell us more about the ritual they were going through and how it felt being an observer with a camera.

There were several rituals they went through within the days I was with them. There were several different pumas (prayers) for the kothi community as well as other members of the temple. There was an animal (goat) sacrifice. There were also rituals that took place in a cemetery and in parts of the village. There was music as well. The festival lasts for over a week so there were many different things that happen within that time.

I’ve made 2 trips to the community, both for about a week. The days were spent doing everything from relaxing and chatting, eating, hanging out, to watching what is going on, and seeing whatever rituals they are performing (when it is festival time).

When it is not festival time, I met several of the families in the community and basically tried to spend time doing whatever they were doing.

“Some khoti are quietly battling with their families about the expectation that they will soon marry and have children, while others are completely estranged from their families as a result of their gender identity expression. They all take what they describe as the female role in sex and give one another female names, by which they address one another.Candace Feit, in an interview with Buzzfeed in April

Closed-off communities like the kothis are slightly different from Hijras, who, in April, were recognised as a third category of gender by India’s Supreme Court. But it’s different for kothis. What was it like to be among people who are so often at the receiving end of discrimination?

The kothis are also a “third-gender” group, so the laws that have recently been passed also benefit them. There are different words used to describe “third-gender” people in India. Hijra is one, as is kothi. Though it is true that Hijras play a different role in Indian society, kothis definitely have their place as well. I would say that all sexual minorities are working hard at getting social recognition and equal rights.

There were many tough stories, and likewise there is a lot of perseverance, love and mutual respect in the community. I was very fortunate to be welcomed very graciously into the group. I feel like I have grown quite close to many members in the community and I am planning another trip back in September to visit them and work on more photos. My hope at that time is to also make more formal interviews with several people in order to better contextualise their experiences. I think the key with this group, as well as with so many others, is that I try to be a compassionate person who has come to get deeper understanding of their lives and experiences. As a result, I was very welcomed and I am grateful for it.

Your works span continents, cultures and religions. What are the sort of things you, as an outsider photographer, have to be mindful about – the customs you have to observe, language barriers or anything else?

I would say the most important thing as I do my photography work wherever I am is to approach all people with an open heart.

To try my best to be patient and really listen when they talk to me. To put people at ease and make them feel like we are exchanging energies, not just taking their picture and not bothering to really work to see who they are. That’s not always possible, but it is definitely always my intention. I try hard not to be the kind of photographer who is shoving a camera in people’s faces in an aggressive way. If people do not want to be photographed , I don’t try to convince them. Though sometimes disappointing, that is their choice and I respect that.