Pulling into the stilted wooden house through a cloud of crimson dust, an ancient-looking man appeared with a cautious smile on his weathered face.

Thick clouds of dust sullied the air, kicked up from the massive dirt trucks speeding by every few minutes at three times the safety limit, if there ever was one. A massive Vietnamese rubber plantation nearby is building new access roads into the small village in Kampong Thom province, an hour south-east of the Angkor Wat Temples of Siem Reap, Cambodia. This region contains most of the last-remaining lacquer trees in Cambodia.

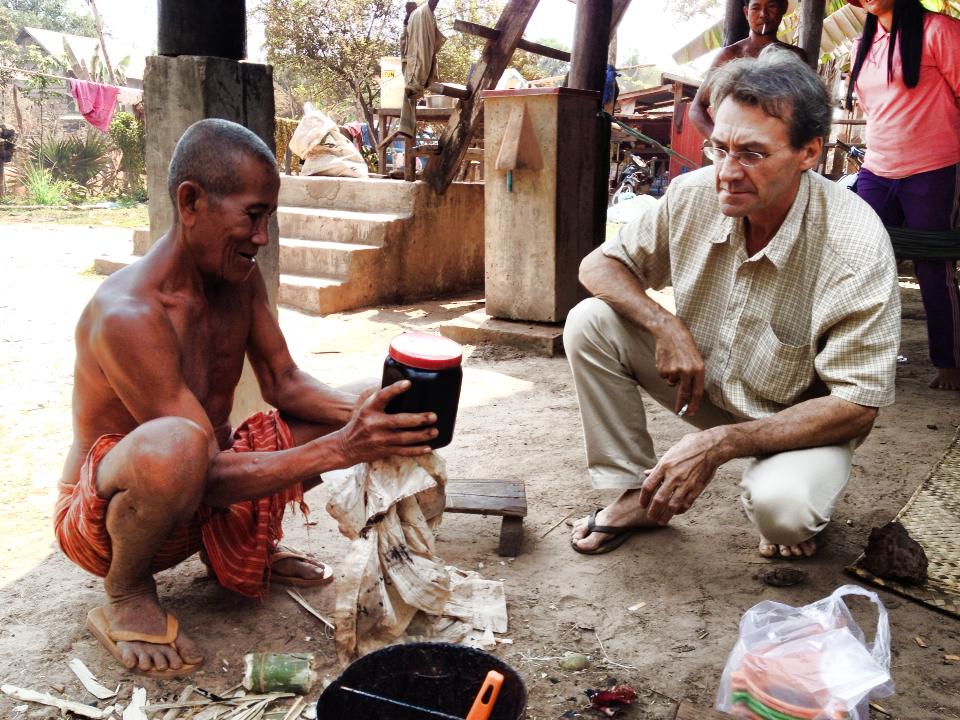

Ta Ly greeted us warmly, eager to show two men his latest batch of pure vegetal lacquer. He is the last of a dying generation of “tree bleeders” of Cambodia.

The men, lacquer master Eric Stocker of Angkor Artwork, and Pierre Mainguy, president of Community First Initiatives, a Cambodian-based NGO helping villagers out of poverty and promoting a Khmer Renaissance, are there to observe and reinvigorate Ta Ly’s laborious and ancient craft – the art of harvesting and processing lacquer essential in Cambodia’s artisanal industry.

An artisan himself of sorts, Ta Ly, or Grandfather Ly, had recently harvested a kilo of the sap, known in Khmer as teuk m’rea, from the village lacquer trees, known by their scientific name, gluta laccifera. The black caustic ‘blood’ of the special tree, when refined into lacquer, has been a key ingredient in Cambodia to coat betel boxes, religious offering trays as well as to coat baskets used for transporting water, fish paste and steamed rice for centuries. Even the bas-relief of the interior stones walls of the Angkorian temples were coated with lacquer to preserve the intricate carvings and Sanskrit scriptures.

These days, pure lacquer is used in electronics for its superior ability to withstand heat, as well as high-end art, refurbishing ancient carvings as well as coating canvas installations.

“I am the old generation and the last one in the village to collect all the sap from the lacquer tree. Big business has bought all the land and the local people can’t get in to harvest the trees.”Ta Ly, the last tree bleeder in Cambodia’s Kampong Thom province

At its peak, Cambodia used to export nearly 50 tons of lacquer to France. After the Khmer Rouge, the craft is nearly lost and the local price for lacquer doesn’t support much production nor the cost of feeding a family after. Modernisation, deforestation and a decline in interest for an ancient craft has also put Cambodia’s lacquer-producing workforce and tree bleeders at risk of disappearing forever.

Stocker wasted no time in looking for ways to improve Ta Ly’s process of tree bleeding, to help the spritely Cambodian man increase his productivity and yield. An enthusiastic man, Stocker is also a world renowned expert in lacquer works, previously commissioned by the Musée Guimet in Paris, France, to refurbish ancient Japanese and Chinese statues with the pure lacquer. As Ta Ly looked on, Stocker went eagerly for a plastic container holding the unrefined lacquer. He patiently explained through Dinez, our translator, that immediately after the sap is collected, it had to be covered to prevent a skin from forming and wasting ten per cent of the product. This time, Eric would strain the sap, removing all insects and bits of twigs, leaves and dirt that had accumulated to educate Ta Ly how to maximise yield and provide a consistent product for artisanal use.

As Stocker continued the process, nearly fifteen percent of lacquer was lost after the initial strain. No problem for now. Stocker was happy enough to find a new stable source for the rare product that was so integral to his craft and to Cambodia’s artisanal trade. He happily agreed to pay for the entire kilo which now was underweight. The next time, Stocker says, Ta Ly would have follow his process to maximise the yield and to earn the price that’s being offered far above the local market rate.

Following Ta Ly through the scorching acrid farmland that appeared abandoned, the Community First team could barely keep up with the 70-something year old. He’d been navigating this land and bleeding trees since he was 18 years old, and his experience and athleticism showed. Scrambling barefoot up the tree, nimble as any tree-climbing child, he gathered the small amounts of sap collected in several small bamboo containers, careful not to let it come in contact with his skin.

“Too much contact and your skin would begin to burn,” Ta Ly said smiling. He has since developed a resistance to the burns from over six decades of collecting.

We looked on in wonder, not just at his agility for his age, but rather, at his almost-instinctive knowledge of how to prolong the life of the very trees he bleeds. Each time he scraped the sap from the twenty or so bamboo funnels into his collection jug, a new incision was cut with a specialised machete to promote new bleeding. Ta Ly’s technique did not harm the tree. He had been taught by the elders before him the careful practice of leaving the tress unharmed.

But for all the care taken in prolonging the life of the tress that breathes life into his way of life, Ta Ly and his craft are in danger of completely disappearing.

“I am the old generation and the last one in the village to collect all the sap from the Lacquer tree,” said Ta Ly, looking down at his collection jugs. “I am afraid that the young generation will not continue. No one will give up the quality lacquer. In the dry season (December through May) the harvest is low. Big business has bought all the land and the local people can’t get in to harvest the trees.”

The local market price per kilo is just under US$5, which takes over a week of labour to collect in the dry season. The trees that aren’t on private property are quite far from the village. Eric, in an effort to preserve this craft, has offered nearly triple the price for a kilogram of lacquer to ensure Ta Ly can support his family and also to encourage the younger generations to take up this craft. Ta Ly sat speechless for nearly a minute as he heard this the news that Stocker and his Angkor Artworks would purchase two hundred kilos of pure lacquer in the coming year. This partnership is just the beginning, and many of the villagers have plots of their own land and can grow new trees by propagation and begin harvesting the sap in around four years.

Community First Initiatives, together with Stocker, today have plans to plant a large scale lacquer tree operation in the near future, one that will not only give fair wages to many Cambodian villagers but to help preserve the dying craft that has been a huge part of the culture of Cambodia for centuries.

Much of this product will be exported to Japan which uses a large amount of lacquer for its industrial electronic production. The income generated will be used to operate other Community First Initiatives to further reduce poverty through education, aqua phonics, clean water and promoting a Khmer Renaissance.

Inspired by these village visits, Dinez, our translator, who is also an Angkor Wat guide and local business owner, has been educating more of the younger generation of locals in Siem Reap city about the importance of these trees and this ancient culture that’s nearly been forgotten.