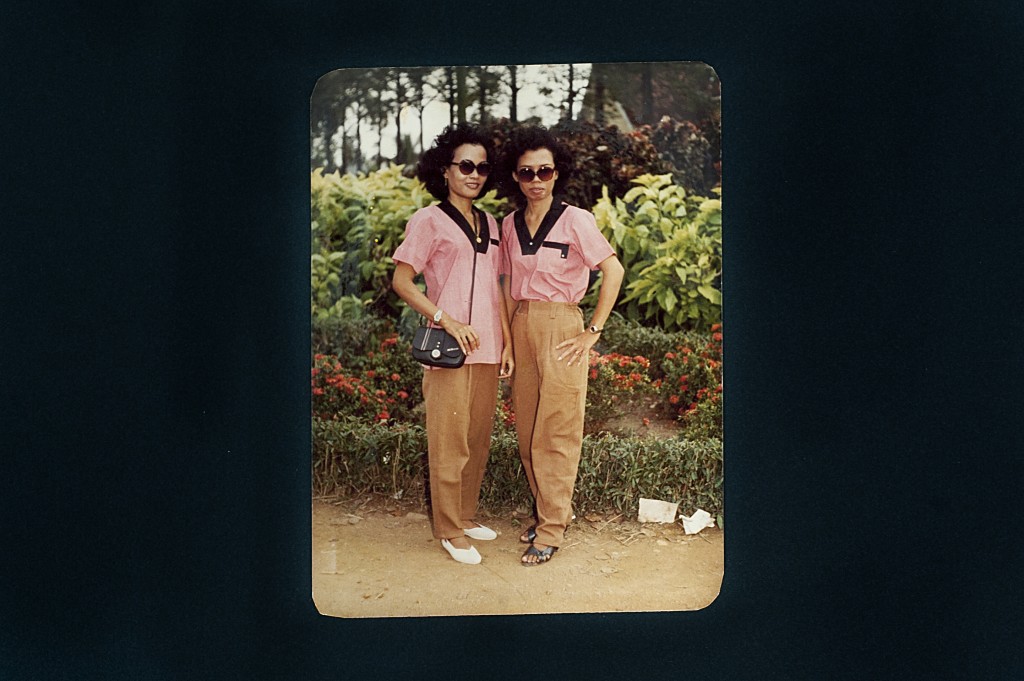

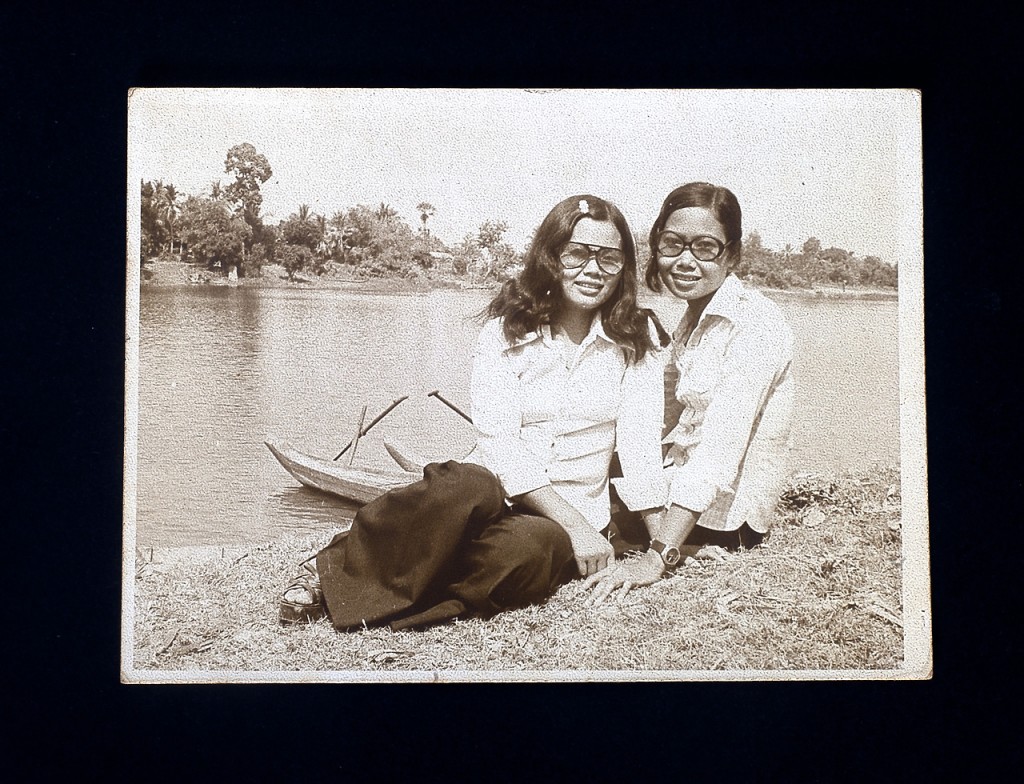

Two Cambodian women sport identical hairstyles, blouses, trousers and shades, posing for a photo in front of a garden of flowers. There is a sense of peace about this shot, but there’s also a surreal disbelief that there they stand, barely a few years after living through a genocide.

And you’d be forgiven for thinking they were twin sisters.

“The two ladies are actually friends and they worked together. The lady I interviewed on the left told me, ‘We are close like sisters, but we’re not from the same family. But we love each other the same, so we dressed the same and it made us feel close, like sisters,'” recalls Cambodia-based British photographer Charles Fox on a Skype call with Contented.

The photo, taken some time in the 80s, is part of an ongoing independent project by Fox who has begun documenting and digitising old Cambodian photos taken between 1979 and 1989. The project intends to document the decade-long period of the 80s when Cambodia and its people began moving forward after surviving a five-year genocide that killed more than a million people in the country during the reign of Pol Pot and the Khmer Rouge between 1975 and 1979.

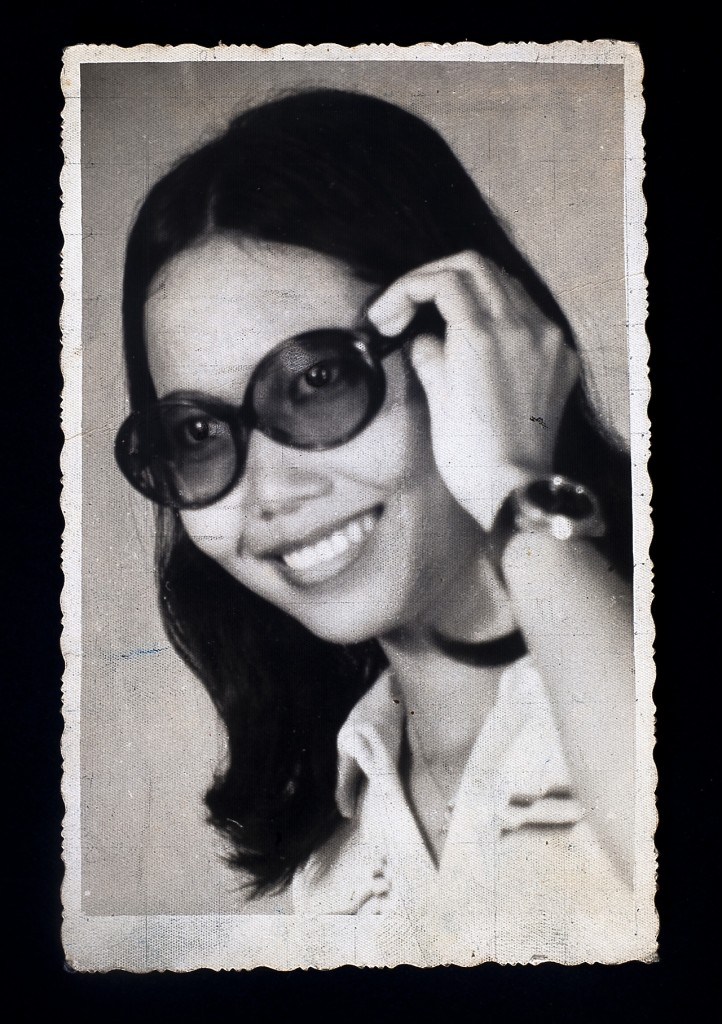

The image, which is yet to be uploaded by Fox on his daily Twitter feed and Tumblr archive, is one of about 300 photographs that the 34-year-old photographer from a small town in Nottingham has come across in the recent months since he began this project. Fox began the archival journey when his close friend, Yanny, showed him an old, weathered ID photo of his father.

“I didn’t start it for any reason other than my really good artist friend introducing me to his old photographs,” says Fox.

“He’s Khmer living in England and I’m English living in Cambodia, so there’s always this really weird dialogue. I guess I really started this project because I was interested about it in the first instance and Yanny was interested when we talked about doing it.”

The project has since evolved into possibly mapping an epoch of Cambodia’s social, cultural and historical change through the 80s.

“Singapore was the first Asian country I visited. Singapore’s changing massively each time I go back. I see Cambodia changing so fast. If I can map some of this change, if I can preserve pictures, then I’ve set out what I intended this project to do,” adds Fox, who has been featured twice on the BBC’s World Service and on The Wall Street Journal for his photo documentations of Namibia’s Himba tribe and Mumbai’s Male Massuers respectively.

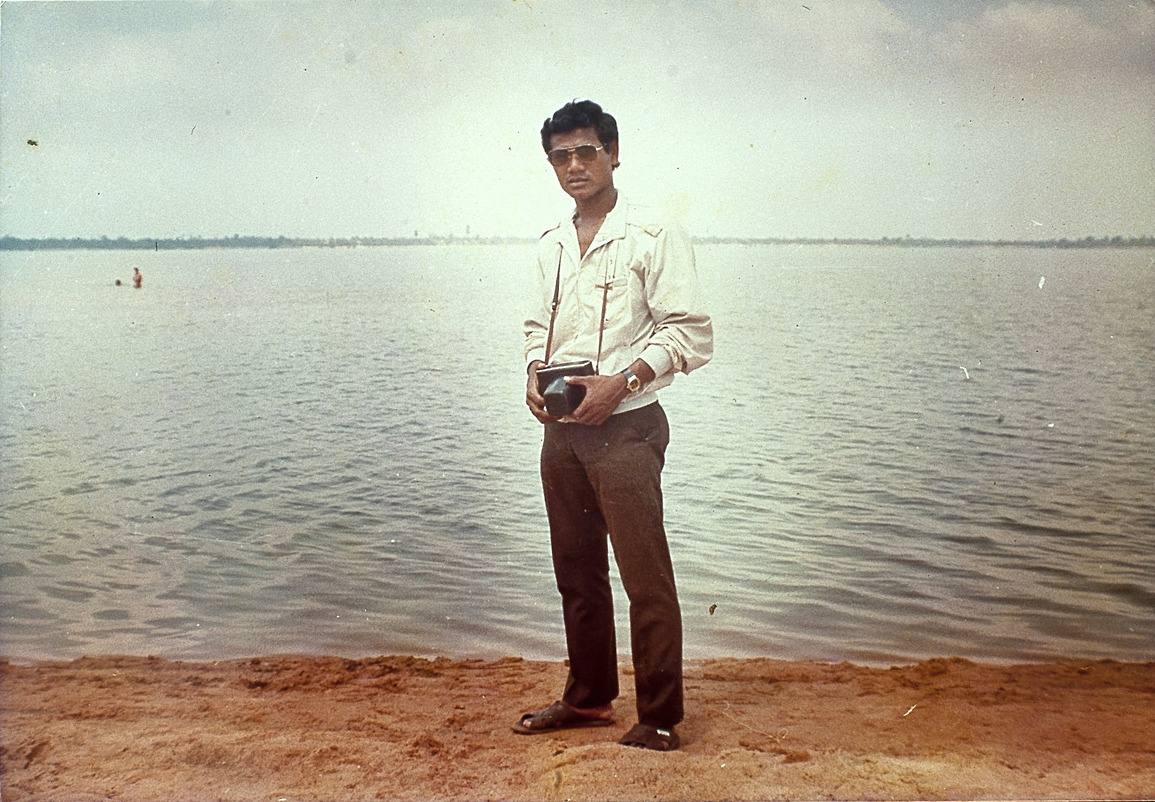

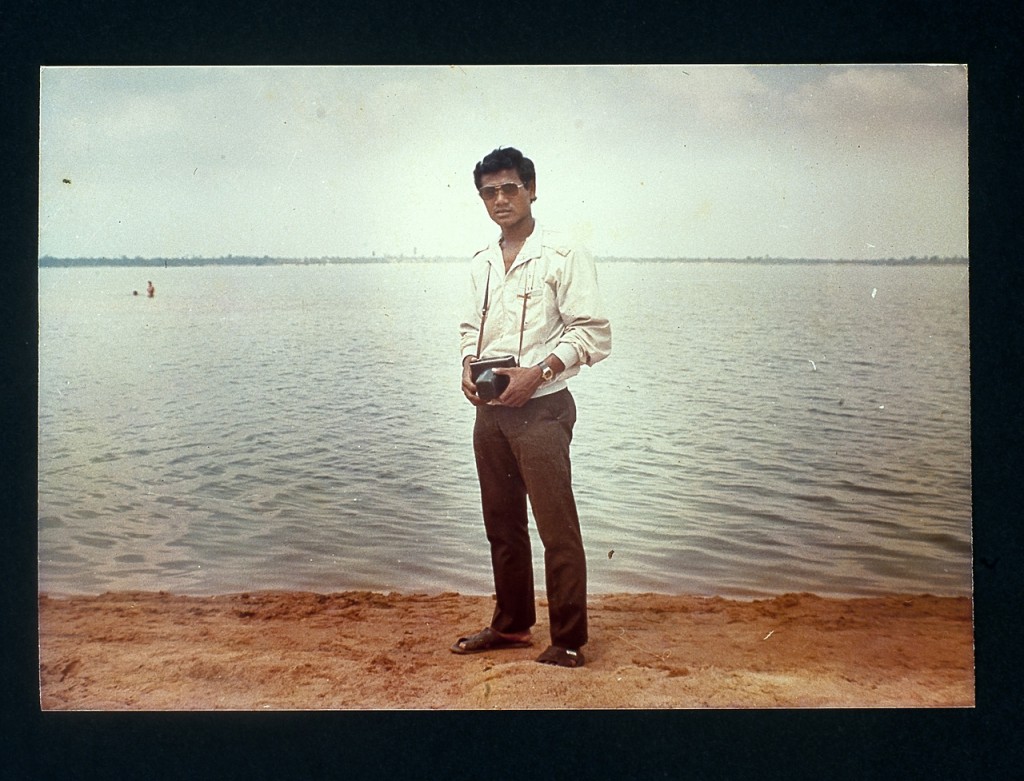

The image of the “sister-friends” is one of the most memorable images that Fox has come across, along with the main photo above of a man posing in Kampot province for an unknown photographer.

“The photograph of the two women was from early on in the project. It’s strange because sometimes you come across a family and everything they have is amazing and this was one such photo,” Fox says.

“If I had been looking for an image that sums up this project in place of words, I guess this is close.”

Fox, who was born in 1979 – the year Vietnamese forces and Khmer Rouge dissidents brought down Pol Pot and the Khmer Rouge – was a photographer and had a full-time career in marketing up to 2005 back in England. He had no real connection to Cambodia apart from a small Khmer population in the UK but decided to leave his job to discover something else on his travels. Chance encounters and friendships during his wanderlust led him to Cambodia.

“It was this plan for going for six months. I was just travelling and met some cool people, followed them and ended up in Cambodia. Then, I just stayed,” recalls Fox.

“At first, I started taking news pictures for local Cambodian papers, then I went back to the UK and I just began to miss Cambodia and its people.”

“Cambodian friends back home look at these photos and tell me they bring back memories of their childhood. No matter how traumatic that period was, in a family photograph or in any photograph for that matter, you have a moment of silence.”Charles Fox, a Cambodian-based photojournalist documenting Cambodia’s revival era

With the project still in its infancy, Fox sources for as many photos from the 80s as he can all on his own. And that means sometimes having to end conversations with the myriad random people he meets with a request for their family photos.

“I would meet people through work and maybe I would go to a corner shop one day and get chatting. Then I would see their pictures on the wall and we’ll talk about that. I would arrange to go back to take a digital photo of it,” Fox says.

But as familiar as he is in Khmer and as socially connected as he is as a photographer working on commercial, journalistic and non-profit community photo projects, Fox goes through his share of rejections and support from the people he meets. And taking a photo is both a poignant moment for him as it is one filled with responsibility, trust and difficulty – having to be someone with a very personal request for the strangers he meets.

“Thanks for asking that question because no one has asked that. The first time you start anything, you stumble and try and find your feet. So the first people I talked to, I asked, ‘Can I borrow these pictures to make a picture of it’ and people were like, ‘No, this can’t be. I can’t let go of this picture.’ I was very apologetic,” says Fox laughing.

Then, he stops laughing and reflects on all those moments of exchange and he pauses for a long period. Finally, his voice cracking from the unrelenting emotional attachment he has developed over a project which he started, he explains that the Found Cambodian Family Portraits is something profound which affects him emotionally and mentally. For him as a photographer, to receive photographs from people who have survived the worst of human atrocities, or to see happiness in these photographs and people who may or may not be alive today, is a privilege.

“I know the emotional connection with photography, that handing over of the photograph,” Fox says finally.

“That physical handover can be difficult and can be emotional. Sometimes these are the only photos they have of relatives and friends. It feels like a massive responsibility handling the photos. It’s a privilege for me to know that it’s a really personal thing to show photographs like that. For me to handle them.”

And while working on a project like this is free of deadlines he so often encounters as a commercial and journalistic photographer, Fox has set himself a daily goal of posting a new photo on Twitter with a brief caption, and a weekly archival on Tumblr. He has since opened up a contributions section on Tumblr to grow the project.

“With anything we do, whether we write or whether we take photographs, we want people to read, to look. My dream for this project would be for Cambodians to interact with it. For them to say, ‘Okay, let’s spark memories to create conversation,'” Fox says as he reflects on the enormity of the task he has set out for himself.

“Cambodian friends back home look at these photos and tell me they bring back memories of their childhood. No matter how traumatic that period was, in a family photograph or in any photograph for that matter, you have a moment of silence.”

To help Charles Fox archive Cambodia’s post-Khmer Rouge era from 1979 to 1989, contact him on his blog here. To view more of his photos, follow him on Twitter and Tumblr.