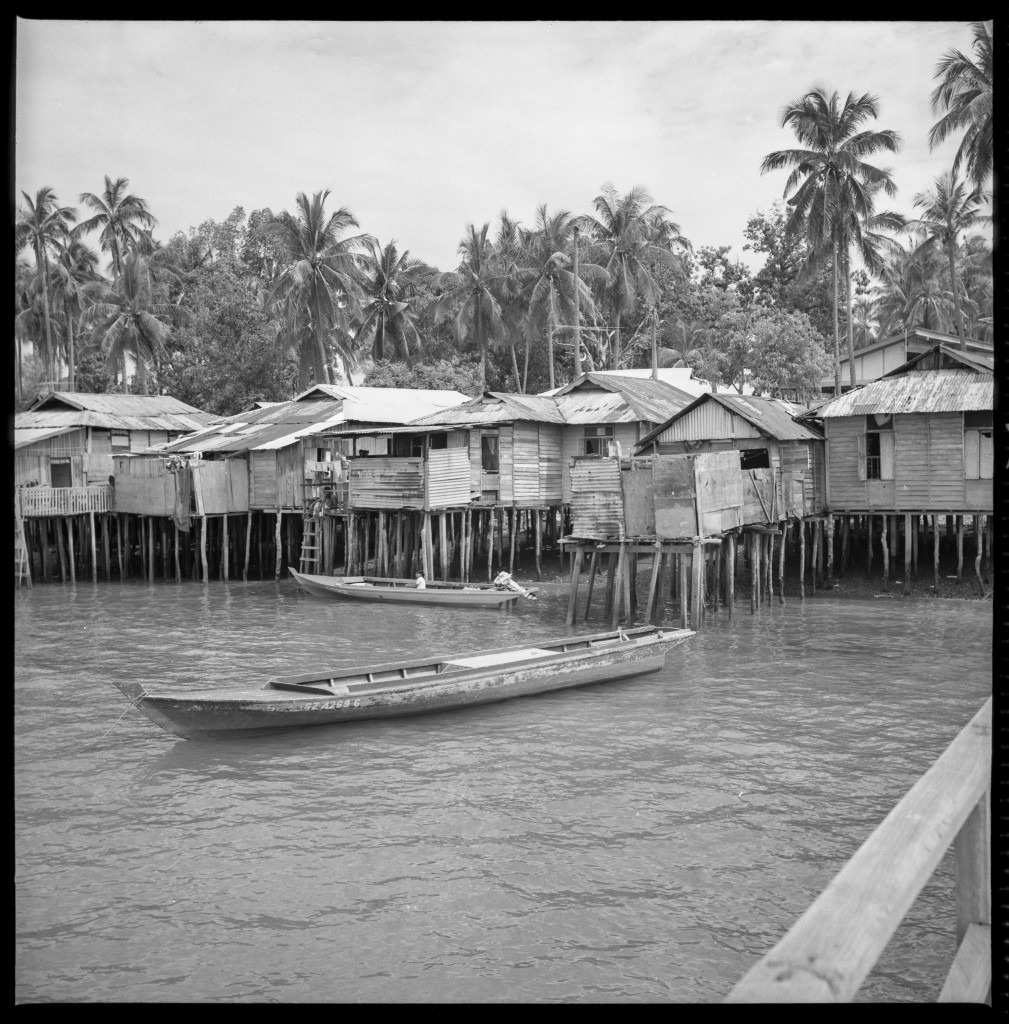

Image courtesy of Geoffrey Benjamin.

Picture a life carefree and idyllic; where you fished for your meals, you could go over to your neighbours’ homes at any time, and a village chief looked after your community.

Now, imagine having to give up the place you call home and saying goodbye to all that you hold dear. It’s not fiction or make-believe. This, in fact, happened between the 1970s and 1990s, right in Singapore’s backyard.

Stories of Islanders

The modern Singapore you know today was home to more than 60 islands, filled mostly with Melayu asli or indigenous Malays, who lived in kampongs and spoke in dialects. By the mid-90s, all of them had been resettled and recompensed in high-rise buildings or what we call flats on mainland Singapore. Yet, there is little mention of this slice of Singapore’s history in textbooks. Has it been washed out at sea or waiting to be recovered?

That is what Island Nation, a documentary project centred on telling the stories of Singaporeans who once lived on the southern islands, sought to uncover. Helmed by photographers Edwin Khoo, Juliana Tan and Zakaria Zainal of local creative agency Captured, they traced more than 100 islanders aged from their 50s to 90s to collect their stories.

“They were surprised that people were interested but had many stories to share still – laced with nostalgia and more importantly, displacement,” Zakaria says.

Once the photographers set out to record the oral history of life on the southern islands, they focused on 12: Sentosa, Pulau Seringat, Pulau Brani, Lazarus Island, Kusu Island and St John’s Island on the eastern side; Pulau Bukom, Pulau Semakau, Pulau Seking, Pulau Sudong, Pulau Senang and Pulau Satumu on the western side.

The Kampong Spirit

What was life like back then? It was a simpler and more rustic lifestyle, austere even, but the kampong spirit (sense of community) was alive and well. “Kampong spirit was there on these islands before the term was even coined. By focusing on the living history of the former islanders whom we can still speak to and interact with now, we seek to capture a narrative that is forgotten,” Edwin explains.

Zakaria adds, “We were curious to learn more about the living histories of people who used to live and work on the offshore islands of Singapore. However due to time and budget, we simply focused on the islands in the South.”

From organising fishing trips with traps called bubu to helping out at weddings, there was a strong communal spirit on these islands. There was even an annual sports carnival called Pesta 5S, which the five islands of Sudong, Semakau, Sakijang Bendera (now known as St John’s Island), Seking and Seraya took turns to host. Over a few weekends, the islanders would play games such as tug-of-war, football and sampan races.

Pulau Seking’s Provision Shop Brothers

The Teo brothers, Teo Yen Eng and Teo Yen Teck, opened a sundry shop on Pulau Seking island in the early 1970s selling necessities such as rice and sugar to the islanders. “We were the only Chinese shop,” Yen Eng noted.

When the islanders came to buy things, they would spend time chatting with each other. One could say their shop was also their home. “In a kampong, everyone is caring of each other,” Yen Eng said. “That’s most important.”

24 April 1994. The brothers remember the date like it was yesterday. It was their last day on Pulau Seking and everything in their shop was given away to friends from the nearby Indonesian islands. Only their clothes were brought back. And yet the most heart-wrenching bit was burning their livelihood – their two boats – as it would cost too much to bring them back on the mainland.

They were among the last families to leave, including the village chief. “None of us said anything,” Yen Teck adds.

“On the island, we were more free,” he said. “We are not free here.”

Pulau Semakau’s Surviving Couple

Even after the islanders relocated to the mainland in the late 1970s, some believed there were islanders who remained on one of the islands. Minah Bte Gap and her late husband, Rani Bin Omar, was one couple that lived on Pulau Semakau for decades, according to newspaper reports.

Despite resettling into a one-room rental flat at Telok Blangah in 1977, they rarely stayed there. Instead their home on Pulau Semakau was a shabby hut by the beach used by workers from the environment ministry. In it were some towels, clothes, a few kerosene lamps and a folding chair – basic items but enough for them to live by.

Her son, Daud Bin Rani, 63, recounts how his parents were never apart and headed out together often as husband and wife. “Jiwa laut,” the former islander says in Malay, which means their hearts were out at the open sea. It was difficult, he adds, persuading them to leave Pulau Semakau.

“Our hearts are attached to the island. We can’t do the same things on Singapore, no?” she said.

The Penghulu’s Wife

With so many stories collected, even more memories were shared by the islanders. Which were the ones that moved the photographers?

“The story of the Penghulu’s wife, Saniah Bte Ali, moved me the most. We were taken aback when she broke down in front of us during the shoot,” Zakaria recalls. On many islands, a Penghulu is known as the head of the village. Saniah’s husband, Mohamed Yatim Bin Akib, was Penghulu of Pulau Seking from 1974 to 1994. In the video, she reminisced how she enjoyed freedom on the island and could take walks wherever she wanted.

“When I remember the island, I feel miserable living here.”

Edwin was touched by the story of the Teo brothers and how their generosity in running their provison shop meant a lot to the islanders. “I think it was especially moving when we witnessed old neighbours from Pulau Seking visiting Mr Teo Yen Teck in his HDB flat during Chinese New Year. When he recalls the eviction, he still breaks down and cries. So it was especially moving seeing his Malay islanders visit him decades later and thank him for being there for them,” Edwin adds.

If anything, the Island Nation project should get one to reflect on the displacement of people in a country, and how important their stories are in relation to the country’s history.

“We want Singaporeans to realise the fluidity of this region with the rest of archipelago and it is best told via the stories of the islanders,” Zakaria explains.

Ultimately, these Southern islands represented an important part of Singapore’s heritage and they are best recounted by the people who lived on them, the islanders.

Discover more stories of the islanders at www.islandnation.sg and Facebook.