At first glance, Hans Chew’s vending machine may not look out of the ordinary. Standing in the School of the Arts Singapore (SOTA), it blends right in to its surroundings – why would anyone bat an eyelid at a vending machine, especially in a school, where most of its students are probably fueled on microwave foods and fizzy drinks anyway?

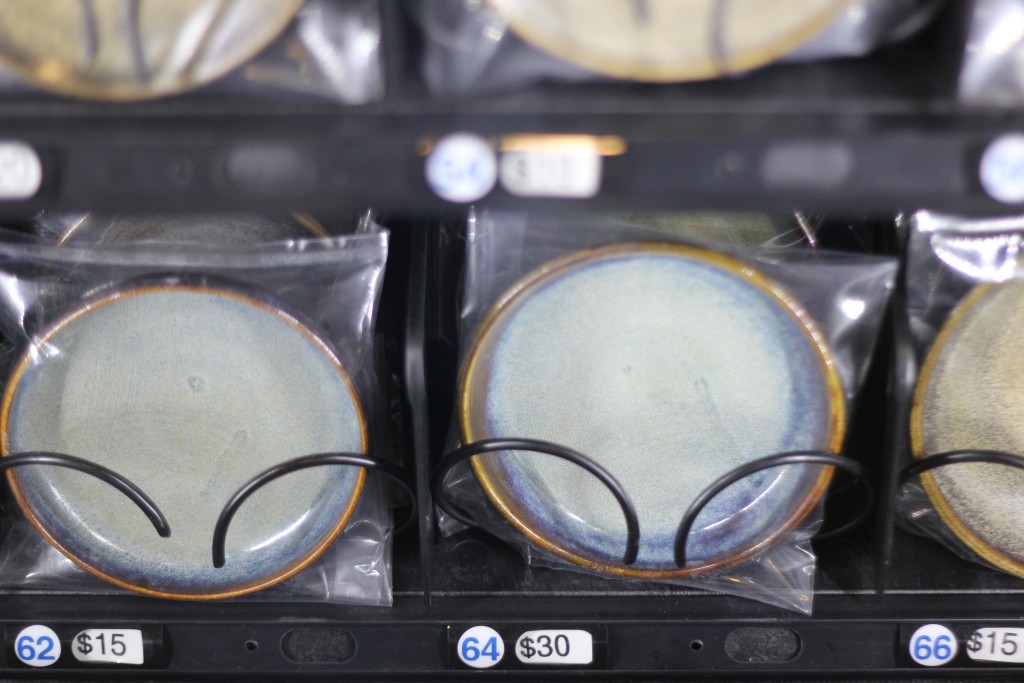

But take a step closer and you’ll find this is no ordinary machine. Because far from your usual soda-dispensing gadget, this particular vending machine houses some 360 ceramic wares hand-thrown by the 18-year-old SOTA student.

Inspired by peculiar vending machines he saw while on a trip to Japan, which peddle everything from your usual canned drinks and snacks to commodities such as lettuce, surgical masks, instant noodles, condoms and even shoes, to name a few, Hans began reflecting on how art – ceramics in particularly – has been commoditised.

“Ultimately we have been very much desensitised from the process of “making” and are fed with this deluge of products that we consume at face value,” he shares with Contented. “Personally, I find it extremely hard to grapple with this issue as I question myself: How is functional crockery made? Where are they made? How are they able to produce them at such a scale?”

So he put himself to the task of creating 500 ceramic wares to be inserted to and, later, dispensed by a customised vending machine.

Though he only managed to create around 360 pieces, know that he was fully involved in the ceramic making process, from preparing the clay, to throwing, trimming, firing and glazing the final product, or products – all within two months.

The idea is to re-create the concept of mass production. Except instead of having these ceramic wares mass produced by factories, you have an 18-year-old student toiling at a pottery wheel for two sleepless months to get his point across.

Sure, he didn’t need to put himself through hand-making each piece, nor did he need hundreds of ceramics. But it was the only way, he says, to “illustrate how the tradition of craft has been affected by the forces of commercialisation.”

“To be able to grasp the magnitude of this, I feel that one has to be fully involved in the entire process of ceramic-making,” he adds. “The procedural experience has influenced the value I attribute to craft and honestly cannot be measured in terms of monetary terms.”

Oddly enough, his biggest concern wasn’t the large volume of ceramics he had to complete in such a short span of time; it was how he could prevent them from breaking when dispensed from the vending machine.

“During the initial stage of this project, I sourced for the vending machine company online and out of the many big names, I found this one company that specialises in unique customisations and machine modifications. They were very supportive of this idea throughout our negotiations and testing sessions.”

To prevent the ceramic pieces from breaking, “I cushioned the fall with sponges and foam and it worked well,” he shares. “Moreover, I had to also consider how the products are to be packed since this project is entirely self-funded.”

Even though this project will eventually be one of the eight works Hans will be submitting for his final assessment at SOTA, he views it more as an independent art project.

“Apart from providing the space for this installation, this project was conceptualised, proposed and executed on my own individual capacity,” he shares. “I do acknowledge the guidance my school teachers have offered, as well as the help I enlisted from a group of friends.”

The spirited young man titles the work ‘Not always $2’, inspired by budget stores that often sell ceramic wares, among other household items, for $2.

“Such practices in the international market devalue the craft and tradition that have been passed down over the generations,” he opines. “I am a big fan of Japanese ceramics and highly respect many of their widely renowned potters.”

What makes his vending machine so special – apart from the fact that it sells ceramics – is that the audience, or buyer, can decide how much they are willing to pay for the works.

“Most of the time in a purchase of something, the transaction is mostly one-directional whereby the shop owner decides on the price and if the consumer is fine with it, the deal is sealed,” Hans says.

“In this work, the audience participation is crucial as they are put through a decision-making process in contemplating the value they attribute to craft in relation to the price they select.”

In other words, the audience is somewhat forced to pause and think about how much they value that piece of ceramic behind the glass wall. At the same time, Hans poses another question to us: “Can we be purely economical about craft?”

Can we really put a monetary value to art? That’s something he wishes to find some answers to with his work.

In the future, Hans plans to work as a craftsman in a ceramics factory to build on his technical skills, and later, study ceramics in Japan “to gain a better understanding of their culture and techniques after graduating from the School of the Arts.”